The case of the seafloor: Where's the fault?

Besides the relative youth of undersea geology, the kinds of extension processes she studies on land also occur at much shallower depths at sea, where the oceanic crust is only 6-8 kilometers thick. That's close enough for mantle rocks to be pulled up by the kind of forces seemingly at work along parts of the massif.

Indeed, plenty of mantle rocks have been brought aboard Atlantis' decks from the slopes of the mountain after trips by the research submarine Alvin as well in dredging sweeps. By comparison, the mantle begins about 35 kilometers below the continents, too far down to be directly accessible.

After almost a month of work over the Mid-Atlantis Ridge, John now feels "the marine geological community may be ignoring the complexity of working here," she said.

Scientists aboard Atlantis have swept much of the mountain with the DSL-120 side-scan sonar in a search for appropriate outcrops and other diagnostic geological patterns. They have begun analyzing the chemistries of recovered rock samples. They are examining the photographs and video images made by the towed camera-bearing Argo II.

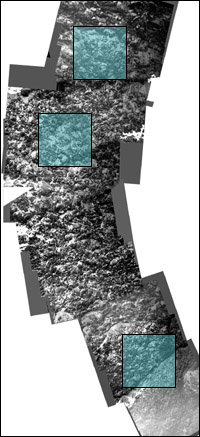

Fig. 5. ARGO mosaic showing ~30 meter length of mantle-based peridotite exposed with joint patterns. Click on a highlighted section for a more detailed image.

With all those high-tech tools, the team is still looking for evidence of a detachment fault where an upward moving footwall and a displaced hanging wall would be separating from each other.

Site conditions haven't helped that quest. A blanket of sediment, which expedition scientists call "the mud zone," cover an area that may separate those hypothesized moving blocks. That's where some furrow-like lines, or "corrugations," dip into a ravine to the west of a deeper back-tilted ridge.

It is easy to imagine those corrugations as scars left on the footwall's upper surface as it moves out from under the back-tilted ridge - the possible hanging wall site. With sediment covering the area, though, scientists have found no signs of the fault that should be there if the hypothesis is correct.

John thinks other signs of a shallow dipping detachment fault might be found near the top of the massif's steep southern wall. That area has been targeted for several visits by Alvin during the past two weeks. But, moving up from below, dive teams have repeatedly run out of time or battery power before reaching it.

She is still hopeful. But with the expedition entering its final week at the site, time is running out. "I always thought things would be simple here but now I know they aren't," she said. "Dogma is being broken."

The hypothesis of the massif's formation was born during a previous 1996 expedition to the site led by Blackman and Cann. At a Saturday, Dec. 2 discussion on the results to date, held in Atlantis' library, scientists were sounding cautious, almost pessimistic, about being able to either validate or disprove it.

"I don't feel comfortable yet that we have a story," said Cann. "The very simple model that Donna and I had may turn out to be incorrect."

An Alvin dive on Monday, Dec. 4 by Hurst and Bacher, the deepest one of the cruise, did not resolve that issue but did prove interesting. Landing at a depth of 3,050 meters on the west side of the massif's southern wall, the pair encountered steep cliffs, huge boulders, and evidence for past volcanic activity.

There were dikes, now-frozen conduits for upwelling magma, oriented in a number of different directions of the compass. That's the kind of setting that is the norm along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where new ocean crust is born within periodically erupting volcanoes. But other rocks found further east along the mountain's southern wall had suggested an alternative pattern was at work there, involving uplift of rocks from deeper in the mantle and relatively little volcanism.

Today's pages:

Drawing parallels | Where's the fault? | Further evidence needed

|

|

|