SDUSD Teacher Professional Development - 6th Grade - Earth Science

March 18th, 2009, Mission Bay High School

Presenter - Memorie Yasuda

Please note that content and links are provided for convenience only. While we do our best to check the quality of our content, we cannot guarantee that it is always correct. We try our best to correct errors as soon as they are brought to our attention so please let us know if you find an error. Hyperlinks that Earthguide provides to external websites do not imply official Earthguide endorsement of, or responsibility for, the content contained on those sites. Links are provided as a service to the user, and Earthguide does not retain editorial control over them. No endorsement of a product or a point-of-view should be inferred.

The atmosphere and its circulation

Atmosphere basics

Where air gets the energy to move

- Energy from the Sun fuels practically all the motion of air, water and life on the Earth, with the major exception being the motion of plates fueled by energy within the Earth.

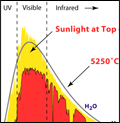

- Energy is emitted by the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation that can travel through the near-vacuum of outer space. Sunlight is radiation.

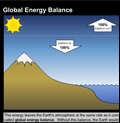

- When sunlight encounters the Earth and its atmosphere, some of it collides with substances in the air returns to space by reflection, or it is temporarily absorbed and then emitted to space.

- Radiation absorbed by matter can raise the temperature of substances. That absorbing substance increases its energy.

- When that same energy is released by matter when it is emitted, energy is lost.

- There is a general balance between incoming and outgoing radiation to space so that the Earth's surface temperature stays relatively constant over time.

- The average temperature of the Earth's surface has varied over a small range over time depending on changes in the reflectivity of the Earth, solar output, and concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

How air moves and why

- Air is mostly heated by the ground.

- When air is heated, it expands, separates from the ground and rises.

- As air rises, it encounters lower pressure and it expands and cools.

- The temperatues at elevation can become cool enough so that water vapor condenses into liquid water. That's how clouds form when moist air rises.

- As air moves upward, its temperature drops by about 6-10° C per 1,000 m.

- The average temperature of the Earth's surface has varied over a small range over time depending on changes in the reflectivity of the Earth, solar output, and concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Clouds and precipitation - where and how they form

- Clouds are made up of droplets of liquid or frozen water

- Clouds form when temperature and pressure conditions are just right for water vapor to change into the liquid of solid phase.

- Clouds form in the sky when air that contains water vapor moves to higher altitude where it is colder.

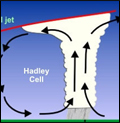

- Clouds form in places where air rises. The places where air rises are associated with low atmospheric pressure.

- Common places where air rises are over the ITCZ just north of the equator, at the polar front, over mountains, in the center of cyclones that are centers of low atmospheric pressure, and over land during the summer when sea breezes and monsoons occur.

Few clouds and little precipitation - where and how this happens

- Liquid water vaporizes as temperature rises.

- When air that contains water vapor moves to lower altitude where it is hotter, clouds tend to vaporize.

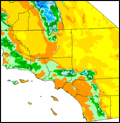

- Clouds tend to disappear in high pressure areas where air falls. This happens near 30 degrees north and south of the ITCZ. San Diego and the Earth's major deserts are at these latitudes.

- The dry part of monsoons and the dryness of Santa Ana winds depend on this phenomena.

Relevance

San Diego water supply and floods

The atmosphere - a personal account while falling through the sky

How different living things deal with conditions at high altitude

How aircraft deal with conditions at high altitude

Supporting science

Questions in science

Image credits

Left-to-right and top-to-bottom:

- Bar-headed goose: Image by World of Oddy.

- Halo jumping Public domain. U.S. Air force photograph of U.S. Army paratroopers jumping from a C-130, flying 25,000 feet over the Arizona desert. Photo by Master Sergeant Val Gempis. From article by Tech. Sgt. Pat McKenna, 1997, A Bad Altitude. United States Air Force.

Conditions in the atmosphere

Conditions in the atmosphere

WebElements™ periodic table

WebElements™ periodic table Ozone in the atmosphere

Ozone in the atmosphere Kinds of sunlight that enters the atmosphere and makes it to the ground

Kinds of sunlight that enters the atmosphere and makes it to the ground

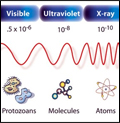

Types of electromagnetic (EM) radiation

Types of electromagnetic (EM) radiation

EM and climate:

EM and climate: EM and communication:

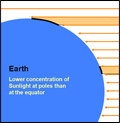

EM and communication: Concentration of sunlight received at different latitudes

Concentration of sunlight received at different latitudes

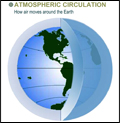

Explanation of general atmospheric circulation pattern on Earth

Explanation of general atmospheric circulation pattern on Earth

Composite animation with significant features

Composite animation with significant features

Why air cools as it rises and clouds form

Why air cools as it rises and clouds form

Clouds continuously forming over the ITCZ

Clouds continuously forming over the ITCZ Clouds at the ITCZ and polar front

Clouds at the ITCZ and polar front

Annual total rainfall across southern California

Annual total rainfall across southern California

Elevation map of southern California

Elevation map of southern California

Air rising as air heats and a seabreeze develops

Air rising as air heats and a seabreeze develops

Where air rises in a cyclone

Where air rises in a cyclone Hurricane Emily activity

Hurricane Emily activity

Historical map of downtown San Diego

Historical map of downtown San Diego Location of early weather stations

Location of early weather stations

San Diego precipitation 1849-present

San Diego precipitation 1849-present

Hatfield the rainmaker

Hatfield the rainmaker

Early dam failures in San Diego

Early dam failures in San Diego

Falling through air

Falling through air Falling through a thunderstorm

Falling through a thunderstorm Halo jumping

Halo jumping

Bar-headed goose

Bar-headed goose Himalayas from space

Himalayas from space

Countries around the Himalayas

Countries around the Himalayas

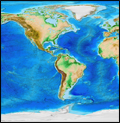

Map of the world - ETOPO1

Map of the world - ETOPO1

No O2, no burning fuel - how high can planes fly?

No O2, no burning fuel - how high can planes fly? SR-71 Blackbird

SR-71 Blackbird

Ares V rocket

Ares V rocket

Coriolis activity

Coriolis activity

Phase changes - H2O

Phase changes - H2O