Rocky Clues

On board the R/V Atlantis, a special team spends much of its time examining how the rocks look, analyzing their mineralogy, and in some cases studying their magnetic alignments too. "All that information is integrated into a preliminary history of what happened to the rocks," said Deborah Kelley, the University of Washington geochemist who is supervising the rock sampling process.

Fig. 2. Heather Hanna and Deborah Kelley removing rocks from Alvin's baskets.

It all begins near Atlantis' fantail after Alvin rolls back into its hanger at each dive's end. Diving scientists cluster with Kelley around the minisub's front plastic sampling baskets to remove the rocks, one-by-one, and place them into separate buckets. Sometimes rock samples get fragmented by the powerful metal claws of Alvin's mechanical arms. In those cases, the scientists are careful to place those pieces in the same container.

Meanwhile, Hanna, a Duke geochemistry graduate student, uses dive records to log the time each sample was collected. Using a magic marker, Hanna writes those times and the dive's number on a slip of paper, which is dropped into the corresponding bucket.

Samples that have been "oriented" with Karson's geocompass get special attention. It is important to know which side of the sample was aligned with that instrument before Alvin's arms removed it. That information will be needed for later magnetic analyses by Gee at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Kelley said.

The goal there will be to compare the rocks' magnetic alignments with that of the Earth. Since Earth's magnetic field has shifted at known past intervals, that information could pinpoint how long ago the rocks solidified, and whether they have shifted or rotated since.

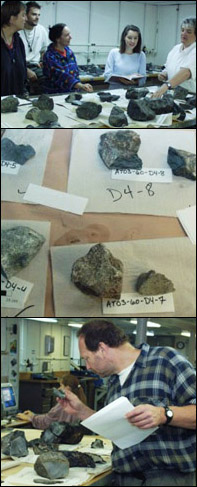

Fig. 3. Upper: John, Schroeder, Green, Hanna, and Kelley go over rock preparation. Middle: Prepared rocks. Bottom: Jeff Karson checks out the day's rock samples. Photos by Monte Basgall.

From Alvin's hanger, the science party forms a bucket brigade to carry the samples into the rock-cutting room, a small laboratory space opening onto Atlantis' aft, starboard deck. There the samples are weighed, measured, and photographed with a digital camera. After that, investigators such as Hanna and Schroeder uses hammers, chisels and a circular saw to cut the rocks up so that the best faces are exposed for study.

While the newly retrieved rocks are covered with a grey-black veneer of iron and manganese hydroxide, the cut faces reveal their real internal structures. The best exposures will clearly show the alignment of "grains" and "veins" in the rocks.

Fig. 4. Heather Hanna slices rocks using a rock saw to expose inner sufaces.

Grains are the crystalline structures that form as rocks cool and solidify from their molten forms. Slowly cooling minerals have large grains; examples include the "gabbros," which form within magma chambers deep within undersea volcanoes. Rocks that cool quickly, such as "basalts" extruded up into cold seawater as red hot lavas, have grains that are much smaller - sometimes too small to see.

Hanna demonstrated how scientists make the grains stand out for examination. They dampen the cut face, either with a sponge or with a lick. The shapes of these grains may be subsequently changed if the rocks are squeezed or stretched by forces around them, Kelley added.

Newly forming rocks also develop veins, cooling cracks that subsequently serve as channels for seawater and mineral precipitation, or for later-arriving molten material that crystallizes there. Those infusions, too, leave a record of themselves in the rocks.

Kelley's team divides up the work at "sampling parties." Kelley and Gretchen Fruh-Green from ETH in Zurich, Switzerland, both geochemists, evaluate how the minerals have been altered by seawater. John and Schroeder, structural geologists from the University of Wyoming, study the rock's appearance to deduce how and why their features have been deformed. Then Kent Ross, a University of Houston petrologist, will look further back to their origins in the magma - "what a rock was like before these other processes affected it," Kelley said."

Their work will be far from over when the cruise ends. So samples will be shipped back to their home labs for further study. Another portion will be sent to Duke, where the samples will be catalogued ("curated") for future reference.

Today's pages:

The Hidden Mantle | Rocky clues | Testing hypotheses, & Imagery | Surprises!

|

|

|