Where we expect things to be

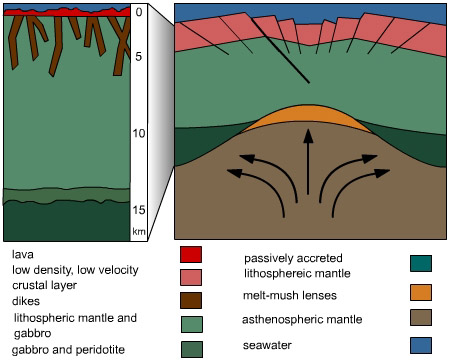

The "normal" structures of newly-formed crust along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge preserve the volcanic plumbing that created them, scientists on the cruise said. At the top are pillow-shaped rocks created when lava emerges like toothpaste at the seafloor. Below that is a network of "dikes," the now-frozen stone remains of conduits that piped magma upwards to extrude hot lava. Still lower are the courser-grained gabbros. And at the bottom are the peridotites, the denser rocks from the mantle.

|

Fig. 5. Vertical arrangement of igneous rock types that make up the seafloor.

|

Testing hypotheses

Testing hypotheses

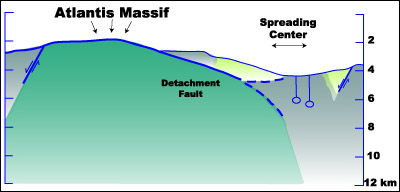

Fig. 6. One of the hypotheses for the formation of the Atlantis Massif proposes that the Atlantis Massif is rising along faults, such as a detachment fault on the east side of the Massif. If so, rock types found at depth should begin to be exposed along the east flank of the Massif (also the footwall of the proposed detachment fault). Will the rocks brought back by the scientists confirm this?

Investigators are testing the hypothesis that this mountain may have formed along a spreading center primarily by stretching and uplift rather than by the typical amount of volcanic activity. In that case, the rocks that are found should have been pulled up from deeper below along a major fault.

That would mean that peridotites from the mantle, and gabbros from the deep crust just above, should predominate in Alvin's collection baskets during dives to the hypothesized "footwall" - the part of the mountain conjectured to have been uplifted. And there also should be relatively few basalts found there.

The first two Alvin dives, made to the steeply cliffed south side of that section, did bring back predominately peridotite samples. But those were too altered by interactions with seawater to reveal much about their original histories, said Kelley and other expedition scientists.

The successful dredge Number 3, made Nov. 28 along that same section's southeastern wall, brought up large numbers of additional peridotites, some of which had a lighter grey color that "tell us some of the initial minerals are still preserved," she added.

"Another thing of interest was that a lot of gabbroic veins are running through them," Kelley said of the lighter peridotites. But so-far "we haven't gotten a lot of gabbroic rocks," she said. "We don't see much of the middle zone, which should be several kilometers thick. That doesn't mean they are not there. But sampling of these rocks has been limited."

As of Sunday, Dec. 3, there have been a total of 9 full-day Alvin dives and two more half-days. The one on Thursday, Nov. 30, ended with a special combination hose and ice water bucket bath for first-time diver Blackman, the chief scientist.

The minisub has visited the "footwall's" southern or eastern faces six times and its dome-shaped top twice.

Fig. 7. Donna Blackman gets drenched after her dive.

An additional Alvin foray went to the "hanging wall," hypothesized as being undercut by the rising, out-of-position footwall. There Cann and Nooner spotted pillow lavas, in a zone where volcanic rocks are thought to more likely occur.

Alvin made another trip to a region between the footwall and the hanging wall, where the scientists are looking for signs of a major fault. While traversing that area, Hurst found some signs of faulting, and more pillow lavas.

There have been two dive cancellations, because of too-high winds and seas. The two half-days were for the same reason. "It's a juggling act," Blackman said at one point, as she once-again revised the posted schedule using both red and blue magic markers.

Imagery

Perhaps the most dramatic discoveries have not been made through Alvin's viewports but rather on the video monitors within the darkened confines of the control van. That's where teams of scientists have so far spent eight nights (between Nov. 22 and today) monitoring returning images from the cameras of Argo II.

The DSL-120 side scan sonar was passively towed behind Atlantis along extensive tracks that crisscrossed the mountain. But Argo runs are far more selective and pinpoint. Their objective is to make a clear and definitive picture of much larger areas than can be seen at once from Alvin.

Link: Side scan sonar

See a section of just processed DSL-120 imagery. Image prepared by Donna Blackman and Scientific Party.

http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/mar/dec5/sonar_scan.html

To do so, Argo pilots from the Deep Submergence Laboratory can move the entire ship with a control room joystick using computerized dynamic positioning in consultation with Argo navigators. And the aft and bow thrusters that control Atlantis are so nimble that the ship can essentially hover in place or even back up in its own tracks.

That kind of deft coordination is crucial when Argo inches up and down just 13 to 16 meters from a near vertical cliff face at the end of a 2,400 foot cable, or ambles up a more gradual slope as the pilot and navigator carefully alter ship speed and cable length.

While the pilot and navigator work the "fish," members of the science party watch live TV video monitors of the ever changing floodlit underwater scene or still camera images that refresh themselves every 15 seconds.

With Argo reconnoitering throughout the night, then being winched-in when daily Alvin operations begin, the scientists are standing three hour control room watches where they log what they see onto computer files, and collect digital tapes of those images for later melding into larger "mosaics."

Since the researchers are doing this in-between their other duties - ranging from rock sampling to "mosaicking" to making Alvin dives - sleep deficits are starting to build and tempers occasionally flare.

Guided by side-scan sonar returns whose resolutions have beefed up via additional processing, as well as personal observations made during previous Alvin dives, expedition leaders are trying to send Argo to the most geologically interesting and relevant places.

Today's pages:

The Hidden Mantle | Rocky clues | Testing hypotheses, & Imagery | Surprises!

|

|

|